‘Black Panther’ Touched Me Deeply and Unexpectedly

Black Panther has been in theaters for three days. I have held my tongue and waited for you all to get apprised for long enough. It’s time to discuss the film as a family.

Black Panther boasts a lineup of some of the most celebrated and talented stars in Hollywood, including Angela Bassett (aka the woman who SHOULD have been cast as Storm in the first X-Men), Chad Boseman, Michael B. Jordan and Lupita Nyong’o. The film also introduced us to equally brilliant but lesser known talents like Danai Gurira, Daniel Kaluuya, Letitia Wright and, *sigh*, Winston Duke.

In my circles, Black Panther was the most anticipated film of 2018. We declared February ‘Black Panther Month’. We anointed the 16th ‘Black Panther Day’. The expectancy was palpable. The movie promised something for everyone, from Blerds to Slay Queens and all who dwell in between, aspects of the film and storyline celebrate the spectrum of what it means to be Young, Gifted & Black.

Though Wakanda is a fictional African country of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s creation, my community has always shared its ideals and mores, including inventiveness, concern for one’s neighbor, respect for authority and the preservation of peace. If you’re reading this and thinking to yourself: “Well, I’m neither Black nor African, and I share these values”, good. That Stan and Jack were able to take these basic, human traits and apply them to an African nation (however fictional) is the point. Storytelling about what it means to live in and be African has been so skewed that for centuries that the rest of the world has looked on the continent with pity and in constant need of pity. We don’t require pity. We deserve autonomy without outside interference.

Naturally, I look at the digital world of Wakanda and imagine what Africa – and its inhabitants – might have looked like without the imposition of 18th century European standards. The architecture of the skyscrapers featured elements of old Mali. The aircraft were designed to resemble scarabs and dragonflies.

Ancient mosque from old Mali. Numerous sky scrapers in the film featured the unique design aspects of this structure.

At the Council of Elders, the leader of the River Tribe proudly wore his lip plate, paired with a three piece suit. To my irritation, the overwhelmingly white crowd in George where I had my first viewing sniggered every time he came on screen, eager to demonstrate their ridicule. Isn’t that the point, though? What is it about lip plates, or piercings or even dread locks that is so threatening to those to adhere to European beauty standards? It’s a question that we are still grappling with today: In what ways do the visual presentation and celebration of my culture interfere with my competency?

Whypipo in my corner of South Africa found this representation of African culture particularly amusing. Damn colonizers.

Of course, there is no logical answer to that; and in the absence of logic, the overlords demand unquestionable fealty in its place.

The think pieces on Black Panther have already come in a deluge, covering the vital role of women in Wakandan society, their counterparts in modern and ancient history, the politics fueling the storyline, and the torrent of white tears that have provided refreshment as we engage in these conversations.

Armed with what little knowledge I had about the character (we mostly read DC comics and followed Thor’s legend when I was growing up) I thought I was prepared for T’Challa’s mythos upon entering the theater. Nothing could have prepared me for Erik Killmonger (born N’Jadaka), son of Prince N’Jobu and King T’Challa’s cousin.

In the film, Killmonger is the product of a relationship between Prince N’Jobu and an African-American woman he fell in love with. After N’Jobu is killed by T’Chaka, Erik is left as a young boy to fend for himself. His every waking moment is dedicated to preparing to exacting his revenge on the royal family, whom he feels has betrayed him. Eventually, we see Killmonger return to Wakanda’s border with the body of Klaw in tow. He presents it as an offering to W’Kabi, who in turn supports Killmonger’s plot to for global domination using Wakandan technology. He justifies this by pointing out that the world is getting smaller, and that there will be two types of people only: The conquerors and the conquered.

“I’d rather be the former,” he says pointedly.

We see in W’Kabi the sort of irrational fear that has gripped much of American civil society today under the banner of Fuhrer 45’s MAGA Campaign. Finctional Wakanda – like real life America – is the “greatest nation on Earth” and yet there are many in power who remain unconvinced of its might. Nakia attempts to make the case that Wakanda can both share its wealth of knowledge and resources AND defend itself from invaders. W’kabi takes the opposite view, fearing that foreigners will change Wakandan way of life. Killmonger, who violently seizes the throne, presents them with the opportunity to see which assessment is right.

In the Marvel Universe, it is often easy to identify the villain and place him/her comfortably in that category. We cheer when the villain is vanquished. It’s what we are supposed to do. I found no comfort in Killmonger’s demise.

Identity

There are many African-Americans (in the literal sense of the term), who were born under circumstances identical to Killmonger’s. My siblings and I were born to a Black American mother and a Ghanaian father. And although we had the opportunity to grow up in Ghana for a time, unlike N’Jadaka, we also had it pounded into us that we were neither American nor Ghanaian enough. This lived experience heightened the impact of N’Jobu’s statement, “I fear you will not be welcome at home. They will say you are lost.”

Abandonment

After T’Chaka kills N’Jobu, he and Zuri leave Erik in America and return to Wakanda. It was a cowardly act. In the film, T’Chaka calls it “the truth we chose to omit”. It would be impossible to explain N’Jadaka’s presence in Wakanda without giving account for his father’s absence. I see the parallels of this act in our relations as Africans on the continent and in the diaspora. As a child with feet in either world, I know how much it would mean to me to be fully embraced by the people who serve as the anchor to my roots. Instead, what we experience is rejection and othering, the result of which is resentment. That resentment still does not erase a desire to connect with one’s roots. Often, it heightens it. There is a need for the abandoned child to prove that s/he is still worthy of acceptance. Sometimes, that manifests in unfortunate ways.

Intrusion

Erik Killmonger is a man who has seen more of the world than most Wakandans have, due to their dogged isolationist stance. He knows that Wakanda has the resources to change the fortunes of oppressed people of color everywhere. He feels that they’ve wrongfully misapplied them. He feels its his duty to right this wrong and orchestrates a takeover. That take over includes waging war on the world, subjugating other cultures and the utter destruction of one’s enemies. In effect, Killmonger is not offering Black liberation as much as he is advocating for the replacement of White Supremacy with Black Dominance. He has become the thing that he hates. As they would, many Wakandans take issue with this. This is not the way things are done at home. Dominance is not a part of their value system.

In Ghana, for instance, we’ve seen this same phenomenon take place. African-Americans and ‘Been To’s ‘ often push their ways into spheres of business and culture, imposing their way of doing things on natives. Each side is convinced that they know better. Far too often, there is little dialogue and more energy expended on fighting for dominance. Instead of strengthened alliances, there is further fracturing. In Wakanda, this played out as a brief civil war. In real life, there is name calling on Twitter. Neither is helpful.

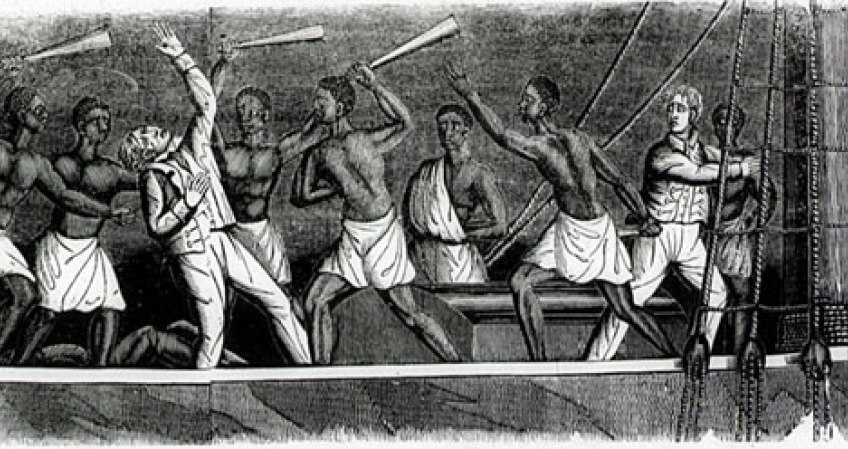

“Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors; the ones who jumped from the ships…because they knew death was better than bondage.”

Sketch depicting a African insurrection on a ship. Image source: howafrica.com

When T’Challa defeats Killmonger in combat, he takes him to a cliff to witness the magnificent sunset that N’Jobu often spoke of. This scene was both powerful and difficult for me to reconcile. It seemed so hopeless…as though N’Jadaka, the lost son now returned home, stood no chance of rehabilitation or embrace. By his own hand, he chose death over bondage, but one would hope that the most advanced nation n the world would have trained counselors on hand to offer him a different path! The weaving of the historical context and the visuals of Africans leaping from the sides of the floating coffins known as slave ships is powerful, but should either of them truly desired it, T’Challa and Killmonger could have found a different resolution to his insurrection.

Or perhaps he was too far gone. We will never know.

There are so many levels to discuss in this film. One could spend weeks analyzing them. But for me, Erik Killmonger’s storyline was central. It was the most relevant to my lived experiences. I know other people connected to it too, for similar reasons. And after all the jubilation and levity and celebration over box office records dies down, the real question becomes: What are WE going to do now?

I believe that’s the query and message that was sent to us all, subliminally.

Leave your reflections of the movie in the comments. As I said, it’s time to discuss the multiple layers of this film as a family!

**Have you been looking for something inspired by the might of the Jabari? Consider this elegant beaded Zulu necklace! Looks great while grunting at colonizers.

https://mindofmalaka.com/product/beaded-zulu-necklace-silver-black/