I am one of the millions who watched Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 Super Bowl Halftime Show this weekend, a performance that has sparked passionate reactions from all who witnessed it. Great art, once consumed, does not leave one feeling impartial, unmoved, or unprovoked, and this show was the essence of great art. Viewers have either declared it the worst halftime show ever or the best they’ve ever seen. It will come as no surprise that I am firmly in the latter group.

Kendrick offered audiences a glimpse into American life rarely seen on a stage as hallowed as the Super Bowl, the so-called bastion of ‘true Americana.’ Whether critics agree or not, a Black boy’s lived experience growing up in Compton is just as authentically American as that of a white boy raised in rural Iowa. Metallica is to America as Missy Elliott is to America. Gumbo is as American as green bean casserole. There is no singular way to be American.

This is the uncomfortable truth for those who claim to have hated the show—those who publicly decried it as ‘woke,’ a product of ‘DEI,’ or something that ‘does not speak to normal Americans.’ This, of course, begs the question: What does a ‘normal’ American look and sound like in their minds? That’s a discussion for another day. Today, I am here to celebrate this performance for the emotions it stirred in me and countless others, and for the teachable moments it provided to those unfamiliar with Black Compton culture or adjacent cultures.

The beautiful thing about culture is that while we all participate in it, we experience it differently. Even within Black America, traditions vary regionally, despite our shared history of targeted oppression and government-imposed barriers meant to keep us in our ‘place.’ Being raised Black in St. Simons Island is vastly different from growing up Black in Chicago.

This idea was brilliantly illustrated in Samuel L. Jackson’s opening act as Uncle Sam. He enters the frame, bellows amicably, ‘Salutations! It’s your Uncle, Sam. And this is the great American game!’ The camera then shifts to Kendrick squatting on the hood of a GNX, launching into a freestyle. Soon after, Uncle Sam chastises him, yelling, ‘No no no no! Too loud, too reckless, too…ghetto. Mr. Lamar, do you really know how to play the game? Then tighten up!’

Just like the U.S. government, Uncle Sam looms over Lamar throughout the performance—praising him when his demeanor is subdued, chiding him when he dares to step out of line. Because this is how the American game is played for Black folks.

The symbolism throughout the performance was powerful and thought-provoking. It evoked nostalgia, offered recognition and redemption, and reclaimed joy in spaces where it had been previously denied. Serena Williams c-walking with unapologetic exuberance was one such moment—an act for which she was publicly shamed when she did it at Wimbledon in 2012. And then, of course, there was the infamous ‘say Drake’ moment.

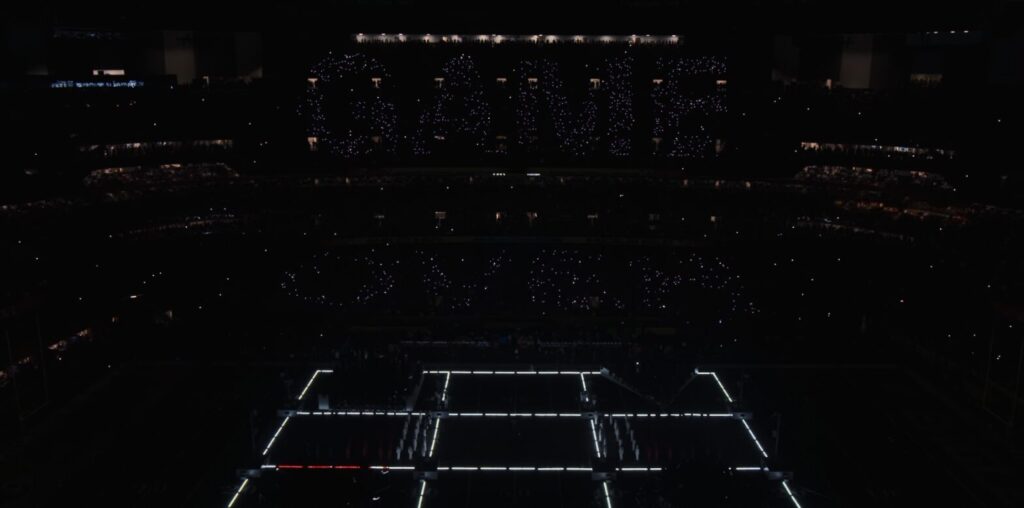

For those who loved the performance, choosing a single favorite moment is nearly impossible. But for me, it was the streetlights that adorned the set.

Streetlights are an integral part of Black urban life. They mark time, serve as tools for communication, and even reflect the level of progress in a neighborhood. Before moving to Ghana in 1988, my family lived in Columbus, Ohio. We didn’t live in a real neighborhood—there was an abandoned car plant across the street, a small block of apartments to the left, and a community college down the road. There were no kids to play with on Jefferson Avenue, so my sister and I eagerly awaited our summers in Detroit, where our family would welcome us for a few weeks.

Junction Avenue no longer exists, except in the memories and pictures of those who lived there 40 years ago. The once thriving working class community was razed to make way for a highway, but there was a time when it was alive with children. We played hopscotch, jumped rope, blew bubbles, and waited for the ice cream truck to roll through twice a day. The kind Arab men down the street sold us bubblegum cigarettes and charm bracelets made of hard candy. A football field sat further down, but I was never allowed to go there alone. The adults never explained why beyond a cold ‘because I said no.’ So instead, Aunt Claire, Aunt Cookie, or Miss Ernestine from across the street took turns watching us from the porch, sipping cold drinks, their presence a silent but powerful form of protection.

When the weather became unbearable or the mosquitoes too relentless, they would retreat inside with a simple command: ‘Come inside when the streetlights come on.’

It was one of my first tastes of independence. As the older sibling, I kept careful watch for the first flickers of the timed lights, ensuring we obeyed immediately. Aunt Cookie did not tolerate disobedience, and one whopping was all I needed to understand the importance of following her rules. But sometimes, I would push my luck—pleading for just a few more minutes to watch the fireflies dance against the concrete. One night when they were on a particularly spectacular display, Uncle Melvin helped me catch some lightening bugs, but they died in the jar overnight. I never trapped them again.

The streetlights signaled the shift in the day’s tempo. Where there had been raucous play and booming music, it was now time for baths, bed, and, most importantly, quiet. I never minded. I loved to read, and my sister loved to color. The grown-ups sent us to our attic room so they could watch their shows in peace. It was a wonderful time.

As I said before, I don’t know what it was like growing up Black in Compton, but I do know that our shared experiences shape our beliefs and behaviors. Coming home when the streetlights came on was a universal rule for Black children across the country—a rule deeply rooted in history. Medical institutions on the East Coast were known to kidnap and experiment on unaccompanied poor and Black children. Word spread and it became a part of our collective culture.

So seeing Kendrick recreate that setting—the porch steps, the streetlights lining the field turned temporary avenue, Black men stationed atop those poles not unlike our auntie gargoyles, witnessing, watching—and then flipping it by staging a loud and defiant performance in the street, when we were all supposed to be tucked inside, quiet and docile? It was masterful.

Rebellion on display.

The streetlights are on and WE ARE OUTSIDE.

The revolution will indeed be televised.

It’s time to stop playing games.